Katie Peterson is the author of three collections of poetry, This One Tree (2006), Permission (2013) and The Accounts (2013). Her newest poems can be found in recent issues of the American Poetry Review, Iron Horse Literary Review, Third Coast, and Grey. She lives in Somerville, Massachusetts and she teaches at Tufts University. She was born in California.

This conversation took place via email in the last few weeks of summer, while Katie was at Deep Spring College and just as we were gearing up for new semesters. I’m excited about this wonderful interview, so full of poets (and ideas about art, experience, and poetry), and which also includes a preview of a collaboration between Katie and the photographer Young Suh.

* * *

MURRAY: I think a great place to begin is with the poem “The Conversation” from This One Tree:

Rain-soaked, the mottled bark

of the flowering pear darkened

past its texture’s vanishing.

My confessions always provoke

someone else’s confessions.

Why do you stand in the kitchen

if you don’t want to talk?

What a wonderful question–who or what is standing in your kitchen (real or metaphorical) at the moment, talking or not talking, or crowding in on your confessions?

PETERSON: The person in the poem is my mother. The kitchen of the poem is the kitchen of the house where I grew up. I don’t have to use the past tense because it is a poem. In the metaphorical kitchen my mother is always present. Before she died there was almost always a “you” in my poems, an addressee, which I (mostly) thought of as a you like Dickinson’s You, that father-lover-authority, the one who might witness you and love you in return. Strangely, in this poem, that “you” is her. If the world presents itself to you as a series of love poems, the world presents itself to you as a series of distances: you hope to discern the squinting of the beloved. In the first sections of the book Permission I can see myself charting those distances, in pursuit of love, urged forward by beauty, often disguised with the language of knowledge. It occurred to me as strange that when my mother died, this figure, this “you” began to disappear from the poems, since I always understood the “you” to be some (male) authority. But maybe it was never so clear in the mind. In a more present-tense sense, now that my mother’s absent, her absence crowds in.

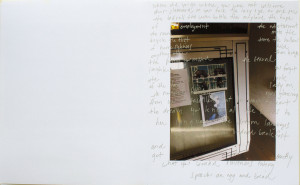

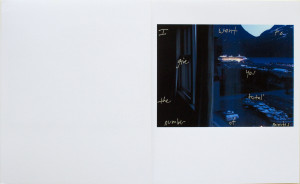

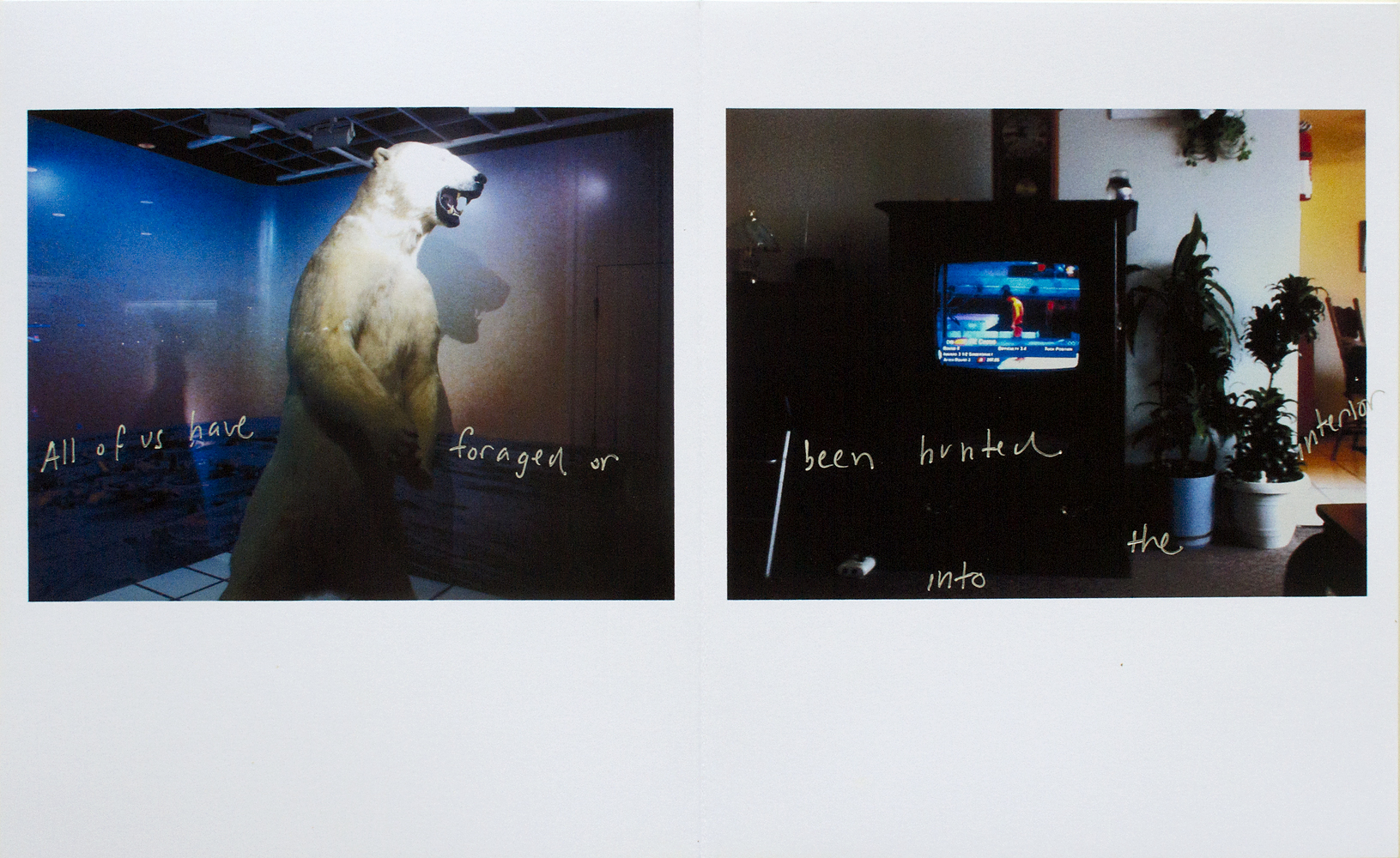

A living person stands in my actual kitchen mornings and evenings this summer: my partner, who is a landscape photographer named Young Suh. My kitchen this summer is the kitchen of a house that used to belong to me at Deep Springs College (I’m here teaching the summer class on “Aesthetics, Ethics, and Community”). Young and I have been working on a number of projects that combine writing and photography in intimate, sometimes destructive ways: I’m writing directly on the photos, in some cases intentionally ruining them. Collaboration in this fashion between us has taken the shape of constant joyful interruption of each other’s tasks. But there is this destructive element – he’ll decide a poem has too many lines, I’ll decide to write directly on top of exactly what makes the photo graceful and elegant. Our subject is ruin in the natural world and we have traveled together to some remote places, including Alaska and the Mojave Desert, to observe and live in nature’s extremity.

The imaginary person who interrupts me these days is the economic anthropologist David Graeber, author of Debt: The First 5,000 Years and The Democracy Project, a memoir of activism before and after Occupy Wall Street that ends with a defense of anarchism. I can’t stop reading and rereading his books and thinking about his insights. He makes the point in the introduction to Debt that debt pre-existed currency and has an emotional component that can’t be reduced to shame, that our debts have historically charted what we value as much as they’ve charted how we are valued, how much banks and culture think we’re worth. I’ve spent most of my life as a poet writing a distanced form of lyric autobiography, engaged in an ostensibly private conversation, but lately I’ve been thinking harder about the larger world – specifically, I’ve been thinking about money. These books help me think, but they interrupt the assumption of my solitude, they keep me from believing in my own independence from any greater world.

MURRAY: I wonder if you feel there is a connection then between the presence of your mother’s absence, as you are aware of it, and the degree to which interruption is informing your artistic experience, either as a collaborator or individual artist.

PETERSON: You’ve made what could be, for me, a fruitful connection, and I’m grateful to you for thinking about it.

Interruptions are part of life, anyone’s life. When I start thinking about interruptions I think of Virginia Woolf who said something like, “for interruptions there will always be” (and there is a lovely book called The Interrupted Moment about Woolf by the scholar Lucio Ruotolo who was kind of an anarchist and therefore understood something about chaos). Woolf, who looked for unities and found fragments. And so the world appeared to me after my mother died. Her death interrupted her own life but it set into motion a constant interruption in my reality.

It certainly is the case that when you are grieving, at first, grief seems the constant and life interrupts, often in the form of the body’s needs (even the saddest person needs to eat). And then life becomes the constant and grief interrupts, and I guess this is supposed to be a kind of progress. It is interesting that my mother’s presence, when it interrupts now, is not necessarily a healthy life-giving image of the real. At times her memory interrupts like a radical might-have-been, a rageful should-have-lived-longer, a peevish why-don’t-I-get-to-be-here, a difficult why-didn’t-you-do-it-this-way. As her presence becomes more and more an artifact of the silence and less and less a set of actual memories (I admit I do begin to forget things, I confess I have probably made room for other things, though the memories I do have appear to grow more like childhood memories, symbolic and strange and big and vivid like dreams), there’s often a wild imagination of what she might be like now that comes in to inform what I imagine. The presence of my mother’s absence gets a bit wilder and more erratic with time. My sister and I love to replicate her tone of voice and her sense of humor. Recently we started making a list of “Things Sheila Peterson Would Never Allow,” most of which she also never could have imagined. Like every life, hers ended with death as an interruption – to make her life, as it was, cohere, it would take an act of art.

* * *

MURRAY: Is there a link we can put up or, even better, are there any images of the collaborations with Young Suh that we could show here?

PETERSON: I’m sending a few PDFS of our collaboration, which has the tentative title of “Correspondence.” We began working on it during a trip to Alaska, which is a messy place and which seems to ask for messy art, messy narratives about itself. I wanted to write a poem in the voice of someone talking to someone who no longer has a home. There’s a way that what I’ve been thinking about is how the opposite of nature isn’t culture (nature always seems full of culture to me) but home. The photos have a lot to do with rapacity, desire and eating. The poem takes the high road and tries to come up with something like a reason for living, but the feeling of the poem is lost, chaotic, unconvinced.

* * *

MURRAY: “Air,” the first poem in This One Tree, observes “Most life stayed put.” Yet the collection ends with “Legend” and the triumphant “look of life unable to sit still,” affirming, I think, the victory of the gaze as an act, an action, of expansiveness and revelation. As you were writing this collection, were you in dialogue with particular poets? Many of the poems express a tension between stasis and growth, or sometimes even seem to posit stasis as a kind of growth. How did you avoid the peril of familiarity taking its toll on discovery?

PETERSON: As I was writing This One Tree I was also writing a dissertation about Emily Dickinson. That humbling experience produced a messy result but laid a foundation for how I would inhabit poems. My interest in Dickinson had to do with how she lived through minute perceptions (the sound of insects, for example, or the awareness of silence) and what she used the experience of the senses for. I saw her looking taking a self away; I saw her gaze unmaking herself in a way; in the poems I could see her removing the first person, the “I,” both over the course of her career (the later poems’ speaker tends not to be an “I”) and in specific poems themselves (in a few significant lyrics, we can see her revising out the first person). I was at first convinced of the moral value of this transaction between self and world as an act of adjustment, a way in to a world without the self as center. Later, I could see it less as a moral endeavor than as a way of surviving experience. So, all half-cracked semi-monastics and contrarian introverts delighted and still delight me: Dickinson, Hardy, Hopkins, Niedecker. Robinson Jeffers. And I would also mention Elaine Scarry’s treatment of beauty across a few works, especially On Beauty and Being Just: her revitalization of the Platonic notion that the perception of beauty doesn’t enable the viewer to objectify but calls the viewer into a position of responsibility and engagement with the world.

For years, I think, I was looking for an answer to the question, “why can’t women write normal poems about nature?” The answer lay in an analysis of the gaze: the feminine self looking always seemed to have a different sense of responsibility and engagement, an ease in self-fragmentation, a rage against self assertion as the primary technique of presence. And so, I could see that stasis, for the monastic, was a form of growth.

The last question is a great question for any artist. I think I can say that whenever I can I throw my lot in with familiarity. Poems show that seemingly basic routines reveal dramatic differences in mood, in thinking, in politics. I suspect you have to give in to the routine and let things be boring sometimes. Dickinson wrote a number of really basic, kind of everyday poems about insects that aren’t that great but the best ones make T.S. Eliot seem like an incompetent preacher. I suspect she had to write both to write the great ones.

MURRAY: “Why can’t women write normal poems about nature”: Were you aware that that was the question you were trying to answer, or did it come as a later realization?

PETERSON: Every time I tried to write a poem about nature it turned out a bit odd! I had an appetite for reality – early on, I wanted to write realist poems (for lack of a better word). I gravitated towards poets with thick descriptions of nature and I often began my own poems with some descriptive impulse – I couldn’t see my own consciousness without material. I bought into the moralism that certain readers of Elizabeth Bishop seem saturated with, that sense of the world needing to be described, in detail, accurately, in order to dignify the poem. I have intense memories of trying harder and harder to anchor my poems in description and the poems becoming more and more untethered from exactly that. Of course I missed the forest for the trees – it’s not description itself but the buried psychology within, the neurosis and the strangeness inside that description. I was aware of the question more in my reading than in my writing, I gravitated towards reading women who tried to describe the natural world and their place in it, and I took note of how those women tended to be less realistic than ecstatic, dramatic (even melodramatic), or hyper-scientific. Hence Dickinson, the mother of all these tones (her prayerful heritage) buoyed by a high degree of skill in describing real life.

* * *

MURRAY: Permission, your second collection, is in part dedicated to Deep Springs College. What are some of the permissions you received there, and what are some of the permissions you gave?

PETERSON: I received permission not to be an expert. It’s a place with no experts: college freshmen drive tractors, and poets teach Nietzsche. Expertise is useless for a poet unless it involves practical matters like fixing vehicles, curing hangovers, or managing personal finances. Maybe an expertise in prosody is also useful, but prosody’s constantly changing, so you better update your software and your user’s manual a lot if you’re going to claim an expertise. At Deep Springs, I suppose, I also received permission to embrace solitude without guilt, which was useful for my future as a busier person. I think I was both giver and receiver of permission in these cases, but the landscape and the community had much to do with it as well. The epigraph to Permission is Robert Duncan’s title: “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow.” I wanted to capture that feeling of returning someplace both natural and bordered, in the midst of wilderness but not wilderness itself. But I was also thinking of Crane’s wonderful lush line, “Permit me voyage love into your hands,” and of Dickinson’s dark sexy quatrains from the poem beginning “They put Us far apart,”

Permission to recant –

Permission to forget –

We turned our backs upon the Sun

For perjury of that –

Not either – noticed Death

Of Paradise – aware

Each other’s Face – was all the Disc

Each other’s setting – saw

All of these – Duncan’s, Crane’s, Dickinson’s – are love poems. In the love poem, the structure of knowledge is the structure of permission – the object of affection permits you greater access as you get to know it, or holds out that promise. But that access often breeds more curiosity and greater distance. And so, the problem of love becomes a kind of epistemological problem. Dickinson’s poem poses the lovers against some authority whose offered permission is actually a form of personal oblivion in captivity – the lovers choose, instead, real oblivion, the “Paradise” of the other, which is transitory (as all experiences of beauty are). Real “permission” always feels at first like an exception to a rule, a transgression.

MURRAY: The poem “At the Window” from Permission begins its final stanza:

Not beauty but eloquence

gets me through the difficult

day: the garden become an explanation

that refuses in all its deep intelligence

to criticize or chasten.

Is there a transgression in the prefacing of eloquence above beauty, and/or is eloquence always (or almost always) a form of beauty?

PETERSON: Our residence with beauty is transient (the beautiful does not promise its permanence). Eloquence is a story you tell yourself that can last a bit longer. Though that story’s a kind of fiction (often a mannered fiction) it can get you through a difficult day. Beauty is the reason for eloquence, but it doesn’t necessitate it. Eloquence may technically always be a form of beauty but it calls attention to itself as something made, forged, told: an account. There may be a transgression in saying that the act of speaking itself, not what’s spoken of, is in more useful than the subject. But Socrates, in the Phaedrus, says that rhetoric is a form of soul-guiding, and thus, rhetoric is not only what we do in politics but in our private lives: the way we talk to ourselves is not some private purity but subject to the same conditions as our other uses of language, like some relationship with the truth, and some yearning towards coherence, and some falling-apart when lies are told. Sometimes it’s a horror that beauty is enough to get us through the difficult day (how many times did people remark on the beautiful weather at my mother’s funeral?) and seeing that, articulating that, can be part of eloquence. Still there’s something suspicious about the word “eloquence,” which doesn’t have the elemental to recommend it the way that beauty seems to. I think of it as worldly, rhetorical, pragmatic, smooth, a smoothing-over.

* * *

MURRAY: I came to a panel you were on that Jill McDonough had organized, and it was called something like Women Behaving Badly, where each poet was asked to talk about something she got in trouble for, specifically in terms of poetry. One of the things I was thinking about was how rarely women are either writing about sex or getting published when they write about sex. From Permission, the poem “Conversation” begins:

Ask me anything. I’ll never say

I don’t want to talk.

This isn’t to say

there’s no principle of selection.

I exclude what I like.

The poem closes with a different sort of conversation:

I’d like to shift

from this shape

not out of hate but from delight.

But I’m not answering

any more questions.

I think you know, from what my legs did

and from what I cried out

how much I’d like

to become something else.

Ask me like that.

I admire the emphasis on like and delight in the expression of physical pleasure here. What are some of your thoughts about sex in poetry, especially by women?

PETERSON: Dickinson mainly spoke of sex in terms of displacement upon the natural world and prayer, but also composed some of the most seductive letters ever written, the missives to the Master. Sex is a great subject and I like it when women write about it. I like it when they address it directly and psychologically, as if it were any other state of mind, as in the still amazing “Mock Orange” by Louise Gluck (“It is not the moon, I tell you. / It is these flowers / lighting the yard. // I hate them. / I hate them as I hate sex,”) or the unforgettable poem “Neptune” by Arda Collins (“The air is made out of statues and dead people // this is why we have sex together”). I like it when women are dirty and frank about it, like Ariana Reines and Rachel Zucker. I also like it when women are still the subject of their repressions and displacements like Dickinson – I’m thinking about a number of the poems in The Errancy by Jorie Graham, in which there seems to be sex behind the poem, and the poem is about making mistakes in perception, or daily life, or some such. In the poems of Sandra Lim, whose book The Wilderness is coming out next year, a sexy turn of phrase will ignite a philosophical meditation and you’ll realize the whole thing was actually a little bit about sex. Sex, like motherhood, occurs to me to be one of those terrains for women where the precedents that exist don’t exert much control over the poems yet to be written. Anna Journey’s poems find sexual occasions that might not have been predicted but tap into some elemental physicality. Sex also seems to me both a public and a private subject because any level of exposure feels like a violation of something (that violation might be pleasurable or no, but it seems to break a confidence). I wrote this poem very directly to someone and it’s exciting to keep keeping the (open) secret.

* * *

MURRAY: Your third book The Accounts has many beautiful and moving poems about your mother’s death. “Argument About Appetite” begins, “When you say, imagine yourself / in a safe green place, I lie / on her grave, looking up.” The poem “The Accounts” closes:

If you stopped to look at the nest

you would see a sleep so purposeful

the ladder of adoration would reverse

and you would stay on earth.

These lines from “Argument About Appetite” put me in mind of Dickinson’s identification of her father after he had passed away as “that Pause of Space.” Also, could you talk a little bit about the purposefulness of sleep in “The Accounts”?

PETERSON: Should sleep have to be purposeful to convince the angels not to take us wherever they do take us when we die? Why is the speaker of the poem making such a case here? Why does she think if she can make an account in which sleep is “so purposeful,” it will work? Her rhetoric is admirable but it fails as of course it should.

We want to fold moments into narratives and make coherence out of them. Lyric poetry can help us take moments and see them in isolation. This “purposeful sleep,” which you’re correct to identify as a kind of euphemism for the dead in the transitional state, was a state of its own. In that nest, the sleeping bird parallels my sleeping mother. Their sleeps – the bird’s on the edge of giving birth, and my mother’s on the edge of death – may be seen merely as transitions into the most important moments of those narratives but I don’t think so. The transitional state exists for its own sake, and is beautiful and human on its own terms. Dickinson’s “pause of space” gives the lie to the idea that absence has no presence. We live with the presence of the dead as a space that loss occupies. I remember my mother’s sleep before death as utterly self-interested, self-occupied. She was concentrating on it, as the mother bird in the nest was concentrating on her job. Moments within the narrative of life, not merely the big finish, not the climax, make existence vivid. They appear to exist for their own sake almost. Sleep, when volitional, can be so magical. Do you know any of those particular individuals who possess sleep like a force of nature, with its own beauty, which is not simply a refreshment of waking or for the benefit of being awake?

MURRAY: Something that Christina Davis said that struck me was “we are always writing at a distance from the next knowledge, and experience is never final.” Thoughts?

PETERSON: At a distance from the next knowledge, the voice is at sea, desperate and resourceful. You want to be doing the most difficult thing, the thing you can barely do. In ballet you want to watch a trained prima and in opera a grand diva but part of the reason in each case is that you’re watching someone do something rather difficult.

* * *

MURRAY: “Elegy” from The Accounts includes these beautiful lines: “The mistake other people make, / I won’t: because the rules have changed, / there is nothing beautiful to obey.” Could you talk a little about these lines or the poem in general? It is a poem I keep returning to.

PETERSON: Is it my imagination or do I keep talking in this interview about things I’ve tried to do and failed to do? I suppose that’s how poetry often feels. In the middle of writing poems about grief I couldn’t seem to write an actual elegy, or what I would have recognized as one. I don’t think this is a particularly good elegy, if an elegy is a poem for the dead. This poem is about me trying to write a poem for the dead. The title announces a predicament “concerning the form of the elegy” in that sense.

I think artists have an appetite for form. Once I described form to someone as “any restriction.” I can recognize form by the restrictions it appears to make. I can see shapes by the permissions they’re granted by form. The speaker of the poem is in distress; she has lost her authority figure, and thus, the force that makes form – that makes restrictions. In her desperate state she is willing to draft anyone (even the reader) to be her authority figure, to be her form-making muse.

I didn’t want The Accounts to just be about my life. An artist never wants that, I don’t think, even if the material comes so much from your life. But I was aided by the totalizing quality of grief – I walked around the world noticing ruin, which had always been there. But I became a keener observer of it. Is it a stretch to say that our sense of traditional authority, in places like the classroom and in politics, has changed for a thousand political and worldly reasons? With no one to guide me I looked to everyone as guide with some terrible hunger.

* * *

MURRAY: In my discussion with Jennifer Moxley, we were talking about the idea of an initial commitment (terms she found too contractual) and poetic trajectories, but she pointed out that honesty in her work, regardless of the form it takes, has been her primary commitment, and that all risk is relative. What are some risks you feel you have taken in your work or have discovered in the work of others?

PETERSON: I want to say that I risk unintelligibility on human terms – that I risk not being understood in my thoughts and feelings. But doesn’t everyone? I think of this as a Romantic risk, the risk that someone like Wordsworth or Coleridge made vivid. I love the poems of Linda Gregg because her style is so clear but her state of mind is often so confused! I often feel like the subject of opposed clarities, be they body and mind, or hope and despair, or joy and sorrow, or beauty and ruin. The poem refreshes these oppositions with the opportunity but not the obligation to reconcile them. If I’m saying I risk not being understood than I’m self-possessed enough, at least in this moment, to admit I wish to be understood, which leads me to believe that I also risk the opposite of unintelligibility, sentimentality.

Women poets take interesting risks. Something I’ve been thinking about in recent years is how women wear their learning – and by learning I mean intellectual knowledge, learned-ness, or to use a more cynical but still appropriate term, “cultural capital.” I’ve been thinking about it because I love books and I love old books best and since they are my companions I like to talk about them and talk to them in poems. Sometimes people find this alienating. I have spent a lot of time thinking about this and though I understand this position (i.e. it’s pretentious or affected to quote someone else or write through myth and literature) there’s nothing I can do about the fact that I’ve been living in books since I could read and I started reading a long time ago, and I’m simply not going to stop writing poems that are love poems to books as well as people. There’s a number of women poets I admire for the way they wear their learning. Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s Heavenly Questions risks a bit of pretension with its kind of baroque, arcane, out-of-fashion surface, full of mythic references and stories. But in speaking through those stories, from Greek to Hindu, she preserves them, she uses them, she gives them to us. Anne Carson comes to mind, too, as someone who risks her readers’ trust by creating such learned and complicated worlds but rewards them every time. Dana Levin, too – she’s brought her readers into her Tibetan Buddhist lexicon while also filling her poems with kitty litter and junk food. I think her thinking is very human. Maureen McLane wants her poems to be both achingly, intimately direct and partake of the world of books and history. Lynn Xu risks being a drama queen about ideas and poetry both: I love it.

* * *

MURRAY: Katie, thank you for joining me. It’s been a pleasure to read your thoughts on poems, poets, and poetry. Speaking of loves (and perhaps transgressions and permissions), could you suggest a few writers who you think it would be interesting to talk to in light of our correspondence? I’d love to continue the conversation.

PETERSON: There are so many and I am away from my bookshelf, but here’s what comes to mind in reference to this conversation in particular. In the last few years I’ve spent much time with Sandra Lim and with her poetry, which combines a stern, disciplined severity with a peculiar vernacular laced with slangy idiom and erudition (her next book, The Wilderness, is set to come out in Fall 2014): she’s someone who understands how much eloquence partakes of grotesquerie. Maureen McLane’s work combines the hum of the mind with a voice that’s always in a body and wears its losses without self-pity (something I’m still working on) – her poems are direct and intelligent. Sally Keith writes like no one else, and her book from last year, The Fact of the Matter, seems really serious when you first read it but teems with every other tone other than serious as you get into it: her modulations in tone educate me. Tanya Larkin lives very deeply the life of a poet, gives herself permission, pays attention to everything, writes surprising work.

Follow

Follow