Sally Keith is the author of The Fact of the Matter (Milkweed 2012) and two previous collections of poetry, Design, winner of the 2000 Colorado Prize for Poetry, and Dwelling Song (UGA 2004); her forth collection River House is forthcoming. She has published poems in a variety of literary journals, including Gettysburg Review, New England Review, A Public Space, Black Clock and Literary Imagination. Recipient of a Pushcart Prize and recent fellowships at Virginia Center for Creative Arts, UCROSS Foundation and Fundación Valparaíso, she is a member of the MFA Faculty at George Mason University and lives in Washington, DC.

Our conversation took place via email during the cold, busy winter months of 2013/2014. It was fun to correspond with Sally, and I enjoyed reading her poetry as well as her thoughts on other writers and artists. I’m also thankful to have a few photos of her collaborative project, El Cuerpo de un Poema, created with her friend and fellow-artist Inma Coll during time spent in Spain at a residency called La Fragua.

* * *

MURRAY: Your first book Design is strikingly interrogative: how do things work, what are they, how long do they last, and how are they composed? From the title poem:

Without wind, description saying nothing.

Even blue skies our mind shrouds

pushing the tunnel further

unraveling the black veil’s hue. We emerge.

And how do I move? How

can I

lift a single foot into this field?

MURRAY: Are questions a function of wind in this book? How do we enter the field?

KEITH: I’m noticing (with some degree of horror) that I have written a lot about the wind, the wind which I found, and still find, so dreadfully violent. Then I was living in a farmhouse at the intersection of four fields; my bedroom was a futon in the middle of the floor, surrounded by large windows that shook as if the house would fall down. Apart from that memory, an ongoing obsession of mine has to do with movement and force. I explore this most blatantly in my most recent collection, The Fact of the Matter, which began as an interrogation of grace, grace as considered by Simone Weil as that which is uncanny in flight. Nothing is that doesn’t move; . . . We must, then, in some strange way, enter what already is. . . . I don’t know how to “enter the field” (or, write a poem) except to find myself there, that is, to have been mysteriously led.

As for questions, specifically, I would say that especially in my first two books, I felt the work of the question like the action of opening a door, or even blowing hard like the wind, and the silence afterward was a space I tried, in my own composition, to hear and record. I am a sickeningly rational person and I lead a relatively ordered life (at least for the moment) but you might not know it from my dreams—thank goodness. It is the space of dreams, the space of that which I do not rationally know, that is essential, even though sometimes I struggle to access it.

MURRAY: I am curious about your phrase “sickeningly rational.” I think I know what you mean (and fear I may find myself in the same category). In fact, do you think most poets or artists secretly locate themselves in this camp?

KEITH: What I guess I meant was just that I wake up to an alarm clock and keep a long to-do list. It’s all so much less romantic than we might have thought. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that most poets are like this, but I imagine those who need to make a living mostly are. I say “sickeningly” because I wish it were otherwise.

* * *

MURRAY: “In Winter” begins, “Underneath, I understand—” as the speaker watches vultures circling. Yet, as in many poems in Design, the speaker reaches a moment of cognitive distress: “I think the body is a spanning, a T. // But my eye is unable. Cannot say. For example, where // does the inward breath end?” I understood the inward breath to be a poetic one, and I wonder if you have any ventures for where the inward breath begins?

KEITH: Looking back, I’m sort of amazed by the relative ease with which I have connected the outward looking (which “is unable”) and the inward breath. And I guess that’s right, if not also paradoxical. I’ve been thinking this morning, actually, about ecopoetics and ekphrasis, in preparation for a panel I’m contributing to at this year’s AWP in Seattle. I realize that it was looking (and specifically at nature) that allowed me the space to write; at the same time, I have always closely aligned the experience of describing with the impossibility of mimesis. In this case, the impossibility allowed for fragments of perception that, once threaded, felt like a satisfactory poetic output. Amazingly, Katie Peterson has described this almost exactly in her interview answer when she talks about dissecting the gaze and the feminine self looking. In sum, looking outward is as endless as that “inward breath” that gathers without knowing how or why. I’ve been reading Marion Milner’s book On Not Being Able to Paint (1950) which has everything to do with the connect and disconnect between inside and out in artistic creation: “what one loves most, because one needs it most, is necessarily separate from oneself; and yet the primitive urge of loving is to make what one loves part of oneself” (78). A similar kind of “double fact” (as Milner calls it) may be that the “inward breath” is breath itself, but to understand it as such would eliminate the bounds of a necessary impossibility.

MURRAY: When I read James Engelhardt’s “The Language Habitat: An Ecopoetry Manifesto,” I was struck by his insistence that an ecopoetics must inhabit both the realm of civic or cultural responsibility as well as the realm of play. Often, we think of these as separate or at least incompatible realms. What are your thoughts on these bedfellows?

KEITH: My first thought has to do with the importance of paying attention, which isn’t easy and, as far as I’m concerned, must be the most essential poetic act. Ecopoetics might inhabit a realm of responsibility simply through describing, if not otherwise presenting, the natural world. I’m interested, after Engelhardt, in thinking about “the realm of play” as a way of more actively engaging. We can think of “play” as both what we do with children and “play” as in to stand in for or to act. Is it not true that most “nature-poems” are neither funny nor imagined into, say, the way a dramatic monologue would be? Keeping in mind that the definition of “ecopoetics” is ever ephemeral, your question makes me wonder about the importance of activating “ecopoetics,” specifically through play.

I recently took a class on the neutral mask, which is a tool actors use to learn to calibrate motion; wearing a leather, gender-specific, mask with a neutral expression, the actor performs a series of exercises that prioritize the idiosyncratic action of the body over the expressive face. One of the course goals was to increase a sense of play (which horrified me!)—we were meant to have fun. And, alas, I increasingly do think that “play” is essential for poetry, especially ecopoetry, which aims to draw attention with the intent to change. My friend, the wonderful poet, Karen Anderson recently mentioned that she gives herself assignments when she is not writing and had, as of late, been inventing names for caterpillars. I loved them! They were hilarious and smart! I didn’t then think of it then, but I find this a great example of what Engelhardt must be pointing toward—an infusing of subject matter with imagination and life-force. It means that the work is real, not merely a rhetoric.

MURRAY: Your observation about looking at nature as being a catalyst to create space to write put me in mind of Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature. Do you know his book? He claims that human activity, sometimes unintentionally but more often willfully, has brought about the “end” of nature as it existed for millennia. That we have replaced nature as nature’s driving force. I’m wondering about how this transformation, if you agree that it has or is taking place, affects our access to poetic spaces.

KEITH: To be short, yes, I think poetic spaces, and all spaces, are shifting radically in this age of living inside an i-phone, if not the computer screen. Sometimes driving to work I think about the irony of travelling through strip malls to get to the computer screen in my office, a windowless room, through which I’ll navigate my day of teaching poetry? It’s as though web-sites are more important than construction sites. It’s crazy making. Of course incredible new spaces are also opening for poetry on the internet, which I benefit from daily. Like all change, probably one shouldn’t call it good or bad, wrong or right, but I will say that I prefer, at least, a window to the real world when I am glued to the computer at home or at work.

* * *

MURRAY: “Morphology” is among many poems in Design that have images of descent and ascent:

Folding segment (of stair) when will you end?

The dream was a ladder (mine, too). Each flight

moves up or down. The understanding lost

and pieces and flight and who is it—

coming down? Rewriting

the letter (again and again) tracing

the madness (desire)

(moves through) to need. Rearranging.

MURRAY: The ladder and dream imagery remind me of Hélène Cixous’s Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. Was she someone you were thinking of while writing these poems?

KEITH: Funny, since you mention it, I have read Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing and have found it enormously powerful. The odd thing is that I read the book years after writing Design so it’s strange to see all these ladders as a way of thinking about desire and need and to so readily sense the connection to Cixous.

MURRAY: Twice this poem gives the beautiful command to “unfinish the floor.” Are there any particular floors you are unfinishing, or attempting to unfinish at the moment?

KEITH: A very meaningful experience to me was the trip I made to Ft. Collins, CO in Fall 2010 to read, at CSU, for my dear friend, Dan Beachy-Quick. My mother was literally dying, though also unexpectedly dying, and I had no desire to leave and felt absolutely no connection or concern for poetry. I remember sitting on the plane and organizing my reading, having decided to read poems that marked my friendship with Dan. What was most notable was that I felt I knew things, in the older poems, that I didn’t know I knew. I was struck by a mystical, almost supernatural, power of poetry. A real exposure of the underneath. In the same way that there were experiences just before my mother got sick that prepared me for her dying, I think I do believe that the self poetry manages to expose is timeless.

To more literally answer your question, I think I am caught in trying to unfinish the idea of what I am or might be as a poet, thinker, or writer. All I am is me, a fact, and how shameful to lose myself to ideas of myself or to large ideas of poetry. To be honest, in those lines, I have almost no idea what specifically I meant or what thinking had possessed me. I was young and was identifying with the human urge to fit in one’s skin, knowing, fully well, the difficulty of it.

* * *

MURRAY: “Orphean Song” has an incredibly plangent ending. Could you talk a little bit about this poem? It’s from your second collection Dwelling Song, and closes:

Dear love: A ladder

in between. One falling to

the other. One drops

a flight of stairs. These are bones

in the sky. Fossils. A broken

cage. Washboard prayer.

A missing tongue, pressing

its only word. Sad and

stammering on—Dear dear:

free, I’m free,

free, I’m asking

KEITH: Reading now, it strikes me that the poem is “about,” if I had to say, a kind of impossibility. All couched in the Orpheus myth, the poem tries to understand longing but also wants to be free of it. The address to the other morphs into a final repetitive knot where the stammering “free” unclogs in the present progressive moment of asking. In the end, not very satisfied—I’d say.

These questions are making me think about angles of approach in poetry. Here, the images and the broken sentences, which highlight in each line a major caesural pause, emphasize fracture: pieces of song. Think of the Orphean head floating, at last, down the Hebrus river after the body has been dismembered. In my first two collections I wanted to fathom the contours of experience rather than to state them, a kind of sidereal making. In Dwelling Song I often made strict, and often irrelevant, formal rules for myself and took pleasure in how the song eked out around those strictures. I am currently, I think, writing poems more rooted in my own everyday life, poems that sound more like my actual speech. Ultimately this progress makes sense to me. Only now do I feel as though I can try less to get at whatever I suppose to be mysteriously lurking because I can sense “it” readily in the mundane, plain everyday stuff. It’s ironic, really. Things simplify, but of course they don’t.

Because, again, there is, (jeez!) a ladder, I find myself again thinking of Cixous . . . In the book’s second section “The School of Dreams,” Cixous describes the mysteries we need as lost and uses the example of the space between a sick mother and her daughter, a mother and daughter because “it’s the most intense relationship, the closest as far as the body is concerned” (89). The poems I have written since my mother’s death are, at least to my mind, utterly different. I haven’t read Cixous since my mother died, but reading this quotation allows me to better contemplate why, for the past three years, I’ve been longing to learn something about poetry through the body, why I have so craved a radically different kind of knowing.

The summer after my mother died I ended up, very much by chance, at a wonderful residency, Fundación Valparaíso, in Andalusia, on the eastern Spanish coast. For the first time, I was too weak to be utterly disgusted with myself when I wrote. (Bad habit, I know.) I didn’t care. I wrote by hand in journals and I went to the beach, where I swam a lot, drank little beers, sat in the sun for too long, and spoke remnants of my high-school Spanish with a Spanish artist, Inma, with whom I fell into a very intense kind of friend-love. It was the first experience of pleasure after my mother had died. I found myself moved by Inma’s work, which is bright and visceral, clearly made more of intuition than intellect. To hear her talk about her process and to see pieces of the world through her eyes allowed me the sense of re-entering the world I felt had disappeared.

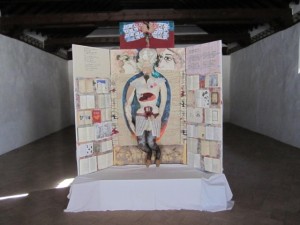

I have returned to Spain for the past two summers. The past July I worked at a wonderful start-up residency in Belalcázar, called La Fragua, on a collaboration with Inma. Together we put together what we called “El Cuerpo de un Poema.”

[Click on Image to enlarge]

To trade lives and art in a broken language (broken because my Spanish is still not good enough to allow for a complex exchange) was inspiring but not without its difficulty—not to mention working in a heat wave in southern Spain. In the end, I felt I had failed at matching the long poem I had written, and subsequently translated into Spanish, with the figure she had constructed, which was sewn together with text, including poems I had collaged from Spanish books; nevertheless, I got strangely close to this world that I don’t know. To me, the experience of trying to do the same things (write, speak, make friends) but in a wholly new context is strongly connected with losing my mother, who I cannot stand to have lost, whose absence still does not make sense and, I suspect, never will.

* * *

On a side note, I’ve just been to the Drawing Center in NY and have seen the fantastic exhibit of Emily Dickinson’s envelope letters, collected in The Gorgeous Nothings (edited by Marta Werner and Jen Bervin). A most memorable letter begins, “we/ talked with/ each other/ about each/ other/ though neither/ of us spoke—.” It doesn’t necessarily make sense to learn a new language, but neither does the nonessential communication one might spend years investing in via poetry. Susan Howe, in the preface to the The Gorgeous Nothings, asks “How do you grasp force in its movement in a printed text?. . .Is there an unwritable unknown poem that exceeds anything the technique of writing can do?” I love that last question. We are all gorgeous nothings, impossible fragments. Whatever I say, surely I’m always asking, if not literally, then through longing, just as any fragment might momentarily stand in for a horizon.

* * *

MURRAY: The epigraph to your most recent collection The Fact of the Matter is from artist Robert Smithson: “Revelation has no dimensions.” This reminded me of Denise Levertov’s emendation of Creeley to “Form is never more than a revelation of content.” How did Smithson come to be a point of departure for these poems?

KEITH: I hope I can remember exactly. As I said earlier, this collection began as a meditation on grace and quickly, then, also on force. I read books on mechanics (I once thought I would be an engineer and so I have some superficial memory of trying to learn mechanics in college) and I read Simone Weil, in particular her essay, “The Iliad or the Poem of Force.” I started thinking about art as action. Around this time I saw a Muybridge show at the Phillips Collection, in DC, and afterward read Rebecca Solnit’s River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West; therefore, I had the frame-by-frame progression of Muybridge’s horse in my head, as well as the history of the transcontinental railroad. I also had seen a small exhibition of David Maisel’s aerial photography, from his series “Terminal Mirage,” in which sites of environmental disaster appear disguised as beautiful swatches of abstract color. In one there was what looked like a tiny fern head, etched in bright red and hanging from some kind of planet or sun. Turns out that was the Spiral Jetty attached to the northern shore of the Great Salt Lake.

Between these exhibitions and writing many of the poems in The Fact of the Matter, I read a lot of Smithson and also took a trip to see the Spiral Jetty. The trip felt to me like a small example of artistic action, though it was nothing compared to the conviction it would have taken to find a truck and driver to dump 6,650 tons of rock and earth into a lake in the shape of a 1,500 foot spiral, which would, in time, become crystallized as the lake water levels rose and fell.

I think about the epigraph variously, but most plainly I think it had to do with the collection as a lyric meditation on fact. Facts are flat and yet they aren’t; everything can be described as fact, and nothing can. (Maisel’s photographs, as it turns out, are a great example of what I mean.) Of course, I like a lot of what Smithson wrote and made, in particular all his meditation and work on “non-sites.” There was a point at which all this thinking looked like it was going to work its way into a book mediating specifically on landscape, taking into account both land art and environmental technology. The poem “On Fault,” which ended up as the last poem I wrote for The Fact of the Matter was a potential beginning for that next project.

MURRAY: “On Fault” perhaps answers my earlier question about responsibility and play—the poem takes a very skeptical look at “the nation’s largest producer of geothermal power,” yet concludes with a sense of mischief. There is a wonderful sense of unsettled possibility in the ending.

“Believe, intend, expect, anticipate, and plan

are all forward-looking phrases,” reads the information sheet.

I hate feeling wary of the things people say.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“We do cause quakes,” is the straight-up admission

of the employee at the plant.

“I hope” is one thing; “I had hoped” quite another.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I saw an orange-red wildflower on the path. I saw a yellow bush.

The pattern of eruptions from California’s Old Faithful

some call a predictor of quakes, though the science is mysterious.

Surrounded by bamboo and pampas grass, tourists sit and watch.

Mount Saint Helena is the backdrop.

That night at the bar when I ordered a glass he brought me a flight.

He did it twice.

KEITH: For me, there always is the problem of using “facts” in poetry, even in using research. Or, there can be. I travelled to Calpine’s Geothermal Visitor Center, just north of Calistoga, CA, with the purpose of learning how the steam fields work; quickly, however, the journey to the information became as important as what I, non-environmentalist, non-scientist, could learn. Even as a very novice researcher it was easy to run into wildly varying perspectives on this supposed environmental technology. I wanted to include the instability of information as well as some of the literal things that happened along the way. I’m still thinking about your earlier question about consciousness and “play.” It isn’t that I feel including information about the bartender, for example, is “play,” but for me it’s a kind of real-life engagement that feels necessary; it is trying to find, and even failing to find, the right context to frame experience.

* * *

MURRAY: Your forthcoming book River House is a beautiful meditation on your mother’s death, and does feel like a stylistic departure from your earlier collections. As you mentioned, there is a bodily aspect to it, and one theme that threads through the poem is the relationship or balance between what is exposed and what remains hidden. Part of what makes River House so evocative is how you convey the sense that it is the small–often ordinary, often physical–experience that is so painful. Section 35 begins:

What once was Kinkos is now Fed-Ex.

Spring classes are starting. The photocopying

Of syllabi I have managed well enough.

Because I work in the suburb where I also grew up,

I think of my mother in almost every parking lot.

And section 39 similarly explores how grief may constantly surprise or overwhelm us in any myriad of seemingly simple acts:

When I eat the bean, pesto, and prosciutto salad

For the first time without my mother, I cry into it.

She used to be part of the world where I am.

I liked the sentences in the Gospel reading, “They do not belong,

but as I do not belong. I am not asking, but I ask you,”

For all the indulgence in contradiction.

How did you decide what to reveal and what to leave hidden? Was it a conscious decision?

KEITH: Funny, I’m now finishing the manuscript and as the work progresses I find myself more and more prone to a checklist kind of regimen (what about when this happened? Surely that was the most meaningful, the most metaphorical…) which I am trying my damnedest to resist. What I’ve enjoyed about the project is how unconscious the decisions about what to include have been. Pieces fell into the poem—or that’s how it felt—and, of course, I was and am struck by the way missing someone so profoundly works its way into the most menial aspects of one’s life: you don’t just sit on the sofa and cry. It has felt enormously satisfying, to me, to try to write about anything and everything, without weighing what feels “poetic.”

MURRAY: Many artists and writers accompany you and your mother (as well as your sister and father) throughout River House. Section 21 mentions the art of Walter De Maria and Agnes Martin:

Driving that morning through the mountains to Taos

I had already visited The Lightning Field,

And wanted to see the Agnes Martin paintings,

Titles like “Lovely life,” “Playing,” “Ordinary happiness.”

I figured a grid might satisfy something.

In my recent dreams my mother has been cured.

You already know the rest. How we all touch and hold her.

How glad we all are. Averted emergency.

The grid seems to stand in opposition to a disorder invoked earlier in the poem, yet something about the concept of De Maria’s land art work felt essential to River House. I kept thinking about them together, each exploring, seeking one kind of hypothetical, as you say, “the notion: for each question / Somewhere there exists an answering voice.”

KEITH: Actually, the trip to The Lightning Field was originally going to provide background for what I thought would be a complement to “On Fault” (referenced above), the poem after the trip to the steam fields. I imagined these as the beginning of a new project, after The Fact of the Matter, originating with the two separate grids—one art and one science, both potentially beautiful, both radical act(ion)s. The experience of visiting De Maria’s The Lightning Field was phenomenal; it may also have felt like the most profoundly meaningless thing I’ve ever done. You can read extraordinary renderings of the experience in Carol Moldaw’s poetry collection The Lightening Field, as well as the art critic Kenneth Baker’s essay collection, published by Dia Foundation. Although I wasn’t sure exactly why I made the trip or if a poem would result, I was compelled by what I knew of the artwork and wanted to see for myself. Most stunning at dawn and dusk, due to mid-day’s flat light blending the poles into the sky, sure enough, still the grid has not stopped resonating. And yet it did what any grid might do: it provided a framework for a space, an inside and an outside.

The time in New Mexico, which appears a few times in River House, was just before we found out how profoundly sick my mother was. I remember driving through what felt like endless land, under a sky larger than any I had seen, and calling my father; I could just imagine my mother there beside him on the sofa, feeling too sick to talk, a situation enacting a distance that was, looking back, ominous. I return to the image and experience of The Lightening Field as mysterious; I still don’t know what it meant, but I know that whatever land the poles grid, is also framed by miles and miles of land without a single boundary line of any sort, barely a tree. Poetry must be like that, also life: we hope to balance our determination with the larger, less known world, a world not yet marked off in lines and rows.

MURRAY: Sally, thank you for joining me and the other poets here. It’s been a pleasure to read your work and to learn about your art. In keeping with your final comments above, would you care to share the names of a few poets whose work you find strikes that balance of determination and ability to explore the less known world?

KEITH: Certainly, though there are many. Influenced by Marianne Moore, Plath, and Gjertrud Schnackenberg, there is the sensational achievement of Robyn Schiff whose poems manage to weave information and experience into sentences shaped by formal restraint but then driven harder by voice. Two recent collections that have stopped me are Catherine Barnett’s The Game of Boxes and Dawn Lundy Martin’s Discipline, which are radically different but both work in series fusing daily experience with a variously rendered necessity for emptiness and gap. I have already mentioned Karen Anderson, who has a phenomenal second collection, Receipt, forthcoming from Milkweed; another poet who I feel very much as my contemporary, and a poet whose work I will always carry close to me, is Suzanne Buffam, whose recent The Irrationalist was published simultaneously in Canada (House of Anansi) and by Canarium, in Michigan.

Follow

Follow